Crossing the gap

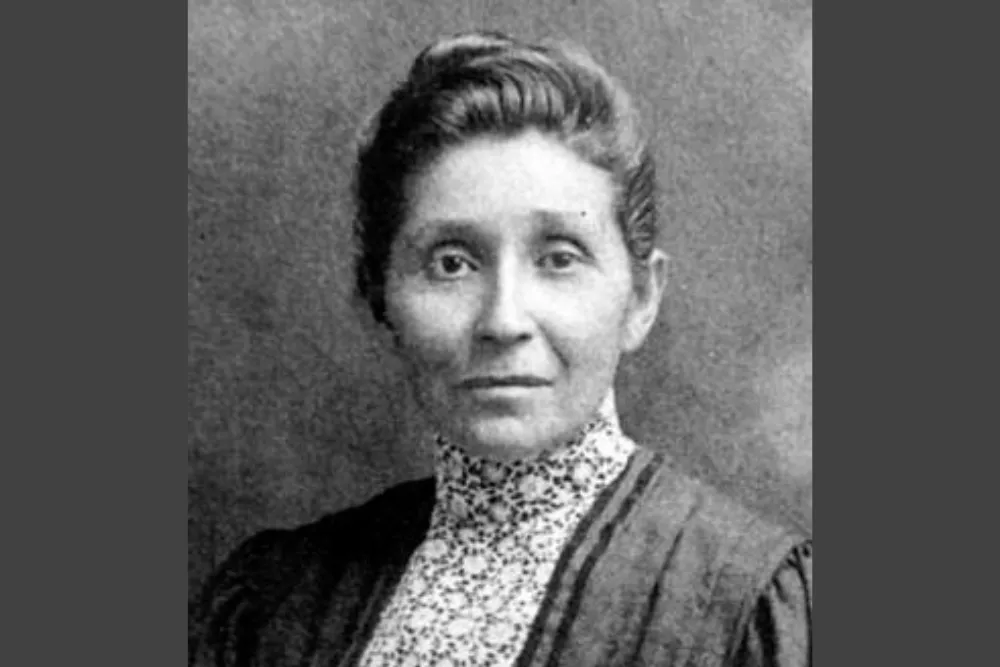

La Flesche’s life was rife with division, even from the start.

She was born in 1865 in the Nebraska Territory to Chief Joseph La Flesche (Iron Eyes) and Mary La Flesche (One Woman). At the time of her birth and throughout her childhood, the issue of how the Omaha People should proceed in light of white western expansion was prominent and often problematic.

A large faction of the tribe felt it was important to maintain traditional ways of life and resist assimilation. Many other members—including, prominently, La Flesche’s father—felt otherwise. They saw progress and potential in adapting to newer practices and technologies.

Perhaps as a result of her father’s strong views, Susan was brought up in a log cabin, as opposed to a traditional teepee, with her family farming an individual parcel in a part of town derogatorily referred to as “the Village of the Make-Believe White Men.”1

But even in that village, Native Americans were treated differently from the white population, a fact young Susan bore witness to one tragic night. At only 8 years old, she stood at the bedside of an elderly Native woman who died in agonizing pain after the town’s doctor repeatedly refused calls to come help.

“[She] was only an Indian,” La Flesche later said of the incident. “And it [did] not matter.”1

Forging a new path

Along with growing up in a more progressive part of the reservation, Susan would eventually be educated in largely-white areas. At 14, she left the tribe to attend the Elizabeth Institute for Young Ladies in New Jersey. She returned three years later and began teaching at the Quaker Mission School on the Omaha Reservation.

It was there she met Harvard-trained ethnologist and women’s rights activist, Alice Fletcher, who would help change her life. At Fletcher’s urging, La Flesche returned east to continue her education, enrolling in the Hampton Institute, one of the most prestigious schools accepting non-white students at the time.

While studying at the institute, La Flesche caught the attention of resident physician Martha Waldren. Impressed with La Flesche’s aptitude, Waldren encouraged Susan to pursue a medical degree at her own alma mater, the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania.

With help from Fletcher, La Flesche secured a scholarship to attend the medical college from the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs, making her the first person in the United States to receive federal aid for education.2 And she made quick work of the program, graduating the three-year course in just two, at the top of her class, before remaining one more year in Philadelphia to complete a residency in the area.

{{link-bank-two-column}}

Building bridges

Upon returning home, Susan found the effects of a changing world were impacting her tribe, whether they were for assimilation or not. Alcoholism ran rampant through the community, with many people pawning off precious possessions or selling land to raise money for more liquor.1 And many others were searching for help or even a safe place to stay.

After going to work for the Omaha Agency, which oversaw the entire reservation, she treated countless cases of tuberculosis and cholera, among other ills, but her service hardly ended there. Before long, La Flesche was offering legal and financial advice and spiritual counsel, along with her medical aid. She quickly became so popular, most patients requested her outright, causing her white counterpart to suddenly quit, and placing Susan in charge of helping the entire tribe.1

With no hospital in the area, La Flesche walked, rode on horseback, or took a buggy to see patients across the 1,350 mile expanse. And, perhaps remembering that tragic night in her childhood, she never refused a patient, treating many white people in the area, as well as Omaha people who were suspicious of her Western education.

Unfortunately, the new-age ills she fought every day followed her into her own home. While Susan eventually married—a part-French, part-Sioux man named Henry Picotte—and raised two children with him, she also nursed him through a long, painful death from tuberculosis, which was made worse by his drinking problem.

Changing the landscape

Back at home, especially after the death of her husband, La Flesche became a political liaison, along with a medical doctor, legal and financial advisor, and spiritual counselor. She began to advocate passionately for temperance, and lobbied Washington to prohibit alcohol on the reservation, eventually persuading the Office of Indian Affairs to outlaw liquor sales there. And she continued advocating community health initiatives that could help heal the tribe—and everyone in the area—as a whole.

These larger dreams of a healthier community came to fruition in 1915, when La Flesche raised enough money to build a hospital in the area. It was not only the first modern hospital on the Omaha Reservation but the first modern hospital in Thurston County, Nebraska.1

Dr. Susan La Flesche died later that year, but not before dramatically changing the landscape of the Omaha Reservation and beyond. With courage and compassion, she helped bring health, safety, and comfort to anyone who needed it, regardless of their background, and through her pioneering example, she helped open the door of possibilities for Native girls to pursue big dreams.