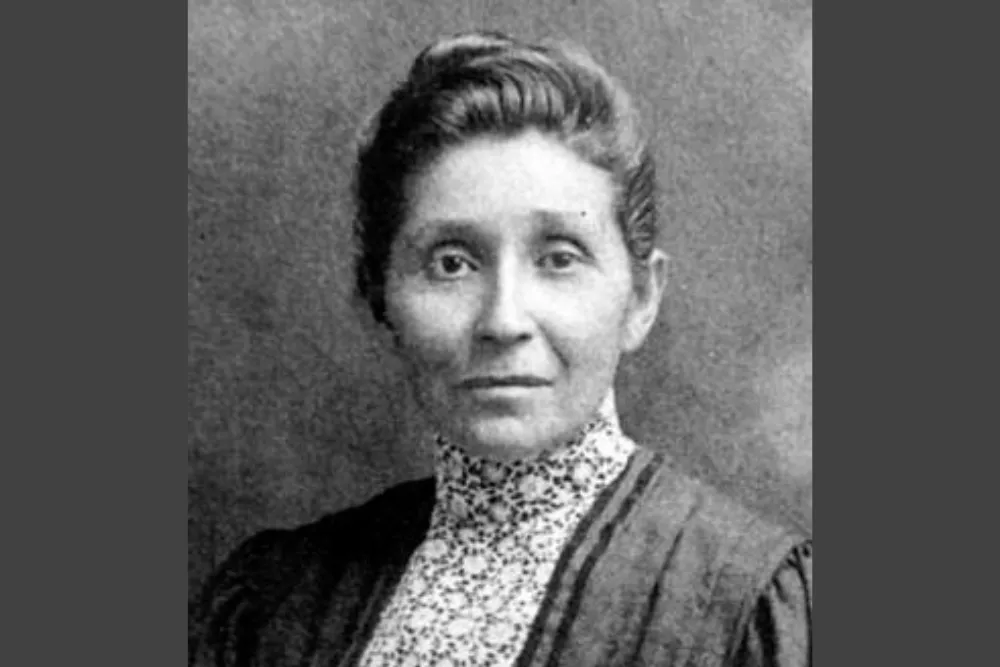

Humble beginnings

Though Susie lived a long life caring for others, her early experiences weren’t always easy.

She was born in 1903 on the Crow Indian Reservation, near Pryor, Montana, to an Oglala Sioux mother, Jane White Horse, and Apsáalooke Crow father, Walking Bear. Sadly, her father died before she was born, so Susie and her sister were raised by their mother and stepfather, Stone Breast.

At 8 years old, Susie began school, as many Native children at that time did, at a Catholic Mission, where Native language, culture, and traditions were denounced and widely discouraged. As one of the only children there who could speak English, she served as an interpreter for her peers.1

Tragically, Susie became an orphan at the young age of 12. At that point, a foster parent from the mission, Francis Shaw, took her in. It was with Shaw that Susie soon left the Crow Reservation and went to Oklahoma, where she briefly attended a Baptist school. And it was with Shaw, then Mrs. C.A. Field, that Susie went East to continue her education at Northfield Seminary in Massachusetts.

{{link-bank-two-column}}

Education

Tuition at Northfield was furnished by Susie’s foster mother, though Susie worked as a maid and nanny to help pay for room and board. Still, Susie reportedly did not like her experience at the school, which showed intolerance toward her culture and background and suspicion toward her as a person.2

Instead, and perhaps to get away from those conditions, Susie left to pursue nursing at the Tall Pines Girls’ Camp in Bennington, New Hampshire, before leaving in 1924 to study nursing at the Franklin County Public Hospital in Greenfield, Massachusetts, under Dr. Halbert G. Stetson.

By 1927, she had graduated, becoming the first registered nurse of Crow descent and one of the first Native American registered nurses in the country. Yet it was not just those accomplishments that made her a pioneer, but the way she would go on to use her education to serve the Native community at large.

Healing a community

Though many of her formative years were spent away from home, and many of the institutions she attended worked to belittle her background, Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail continued to hold on deeply to her heritage and identity as a Native American. And it didn’t take long for her to show this through her work as a nurse and caregiver.

After briefly serving tribes in Oklahoma and Minnesota, Susie returned to Montana in 1929, taking a position at the Indian Health Service’s Hospital at the Crow Agency. She bore witness there to horrors like the forced sterilization of Native American women, Native children dying from lack of access to medical care, and tribal elders suffering in health due, at least in part, to difficulty communicating their needs to Western physicians.

Not long after returning, she became a consultant for the Indian Health Services, traveling around the country to document these and other threats facing Native peoples. Her analyses were eventually relayed to Washington, and Susie was given a position in the Division of Indian Health. This enabled her to bring public health projects to reservations across the country, such as access to clean water, sewage disposal, and garbage disposal.

Not long after returning, Susie had also married a fellow Apsáalooke Crow, Thomas Yellowtail, who would go on to become a prominent spiritual leader of the tribe. Through their marriage, they continued raising awareness of Native culture and the challenges facing Native people, including by serving on education councils at the tribal, state, and federal levels and by going on tour through Europe and America with the Crow Indian Ceremonial Dancers.

Laying the groundwork

Along with bringing large-scale projects to enhance public health, Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail continued working diligently to serve individuals. Her work and advocacy helped usher in a number of changes in the way Native people were treated, including allowing Native healers to attend to patients and improving communication between Western doctors and Native patients.

She was awarded the President’s Award for Outstanding Nursing by President John F. Kennedy in 1962 for her service. Throughout the rest of her life, she continued serving on committees and hosting educational summits to bring awareness to the needs of the indigenous community and bring improvements to reservations across the United States.

Shortly before she died, she founded the first professional association of Native American nurses. She was officially dubbed the “Grandmother of American Indian Nurses.”2 Today, medical schools everywhere teach the kinds of practices Yellowtail instituted so long ago—the power of addressing a patient’s spiritual and environmental concerns along with their physical care.

Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail was not only an early pioneer of holistic health but also an example of the strength, love, and advocacy needed to improve outcomes for every patient. And though she passed away in 1981, her example thankfully lives on.