Laying the groundwork

Phipps Clark was a trailblazer almost from the start.

She was born in 1917 in heavily-segregated Hot Springs, Arkansas. Yet, despite the real and dangerous boundaries she encountered on a daily basis, she was able to excel, particularly when it came to school.

Her natural intelligence helped her graduate from Langston High School, a segregated school for African-American students, considered one of the leading institutions of its kind at the time. She followed that up with an education at the prestigious Howard University, majoring in mathematics and physics, two highly unusual fields for women, especially women of color, to pursue in the 1930s. She would go on to graduate magna cum laude.

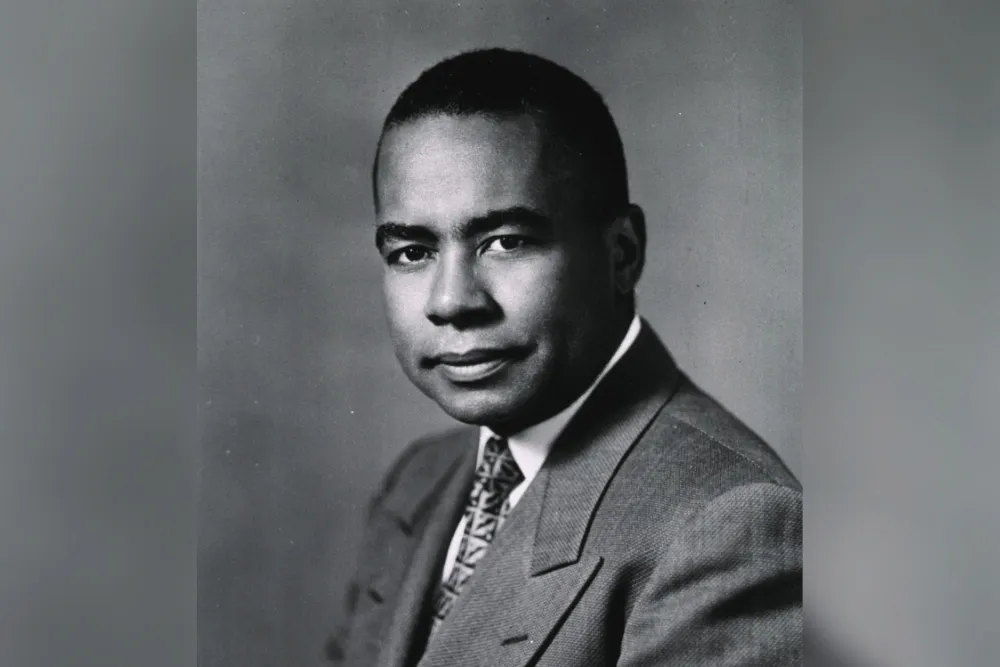

It wasn’t until later in her college career that she started considering psychology, the field in which she would produce her most impactful work. Interest in the subject began when she met her future husband, Kenneth Bancroft Clark, who was pursuing his master’s in psychology at Howard.1

Phipps Clark would follow in her future husband’s footsteps, going on to earn a master’s in psychology from Howard herself. The pair, who would become collaborators on a number of studies, both received doctorates in the subject from Columbia University, the first Black man and Black woman to do so.1

{{link-bank-one-column}}

Building a community

Despite her excellent educational pedigree and research background, Phipps Clark had trouble finding work as a Black woman in the 1940s.1 She eventually became a counselor at the Riverdale Home for Children, a New York City-based establishment dedicated to caring for Black children.

The experience would go on to profoundly shape her thinking and career.

Working primarily with homeless Black girls, Phipps Clark began to notice patterns of an inherently flawed system that failed to provide adequate social services for minority children.1 So, in 1946, she addressed these issues more directly, opening the Northside Center for Child Development alongside her husband.

The first establishment of its kind, the center provided psychological and social services for minority children in the Harlem area.2 Showcasing a perspective ahead of its time, Phipps Clark veered from the prevailing psychoanalysis-focused approach to incorporate more holistic services at the center, including schoolwork support, vocational guidance, and various programs for parents as well.2

Phipps Clark and her husband also used the center to run several psychological experiments, including the analysis that would become their most famous work.

Breaking a system

They were called the “doll tests,” but the unassuming toys at their center would be elevated to immense tools for exacting social justice.

Conducted at the time the Clarks were running the Northside Center for Child Development, the tests were designed to assess a child’s racial perception. Four dolls, identical except for color, were presented to children between ages 3-7, with the children asked to identify the race of each doll, point out which they preferred, and explain why.3

A majority of the children, all of whom were of ethnic minorities, said they preferred the White doll, assigning it many positive characteristics.3 The Clarks theorized that this was the mark of prejudice, segregation, and discrimination in society, with Black children internalizing feelings of inferiority and developing lower self-esteem as a result.3

The findings were heartbreaking, but they would play a significant role in ending at least the segregation that helped lead to such results. In 1954, the doll tests became a pivotal argument in Brown v Board of Education, the famous Supreme Court case that desegregated schools in America.

The doll tests would help all nine justices agree on the unconstitutionality of “separate but equal” schooling, with the case’s decision explicitly stating that the practice was likely generating feelings “that may affect [children’s] hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.”3

Brightening the future

The doll tests may have been the most visible work conducted by the Clarks, but it was far from the last they would contribute, either to the field of psychology or the Civil Rights movement.

The couple would continue using the Northside Center for Child Development to help children in need and help study the psychology of racism and discrimination. In 1962, they launched the Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited project (HARYOU).1

Acting as almost a supplementary service to the Northside center, HARYOU provided additional help with schoolwork for students, job training opportunities, and programs to help Black residents navigate various government agencies to receive appropriate services and compensation.4 A series of financial and political issues led the project to ultimately be short-lived, but not before it helped numerous community members and drew the attention of Civil Rights leaders like Malcolm X.4

Mamie Phipps Clark died in August 1983 at age 66. But she left behind a profoundly changed society, thanks in large part to her pioneering work.

The strength to persevere through her own experiences with discrimination, especially as a Black woman in the sciences, helped her erode those same types of attitudes for future generations. Her ethics and intellect helped her use psychology to its fullest potential: as a tool to spread understanding, empathy, and the social justice that can flow from broadened perspectives.