The first of many firsts

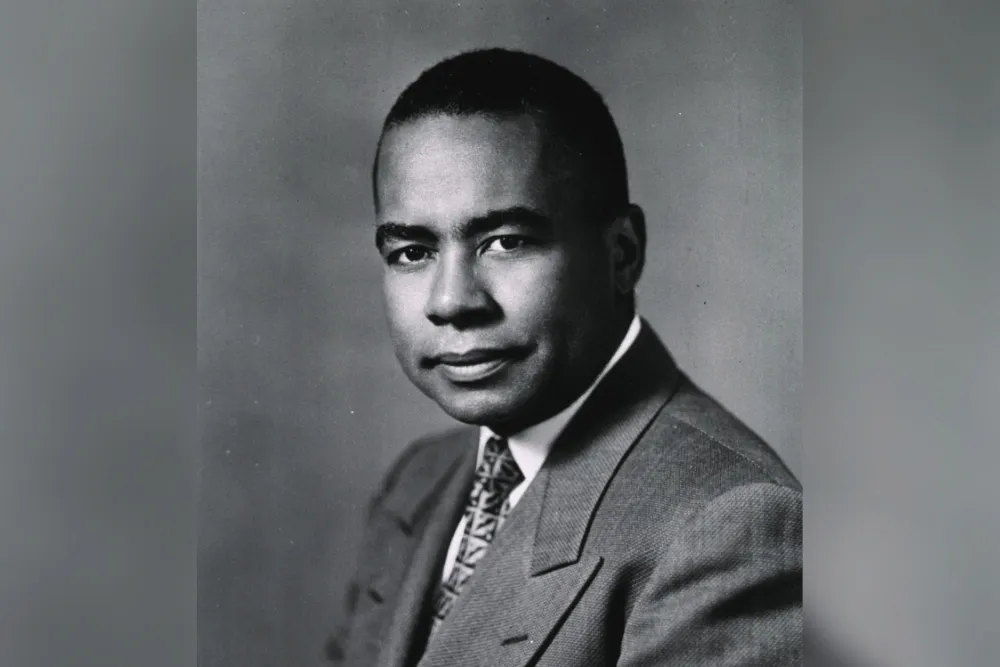

While Dr. Cornely would go on to make history in the United States, his story actually starts far away from the continent. He was born in the West Indies, on the island of Guadeloupe, in the city of Pointe-a-Pitre, on March 9, 1906.

Still, his family moved to America early in his childhood. Cornely lived briefly in Harlem, New York, before finally moving to Detroit, Michigan, in 1920, where he would spend some of the most foundational years of his life.1,2 In fact, it was in Michigan where Cornely got his start on the many “firsts” that would come to mark his career.

He enrolled at the University of Michigan—one of the few colleges accepting Black students at the time—going on to graduate in 1928 before deciding to further pursue his education there, matriculating to the university’s medical school. Before leaving with his MD in 1931, he became the first Black American student at the school to be elected to the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society.3

But he wasn’t nearly done with his “firsts.” Dr. Cornely continued his education at Michigan, going on to earn a PhD in public health in 1934, the first Black student in the United States to hold such a degree.2 And he would use these accomplishments to try to create an even bigger first for society at large: A healthcare system that served Black and White individuals as equals.

Breaking down barriers

Interestingly, through a large portion of the time Dr. Cornely studied at Michigan, the University was led by president C.C. Little. A controversial figure, Little was a vocal proponent of eugenics, a concept focused on arranging human reproduction to “better” the species by perpetuating certain genes or characteristics.5 The idea was sadly widespread and accepted at the time, before being almost universally denounced after it was adopted by the Nazis as a blueprint for their genocide in the 1930s.4

It’s unknown whether Little’s worldview influenced Cornely to become a resounding counterpoint in society, but the doctor did go on to accept an assistant professorship at Howard University's College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., where he was a celebrated teacher and researcher.3

It wasn’t long before Cornely became department chair, and by 1947, he had added medical director of Howard's Freedmen's Hospital and chief of Freedmen's Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation to his resume.3 All the while, he kept accumulating more “firsts.” Dr. Cornely became the first Black American to be elected president of the pro-National Health Insurance Physician's Forum and the first Black American to chair the Medical Care Section of the American Public Health Association (APHA).3

And after all that, he was just getting started.

{{link-bank-one-column}}

Medicating a movement

Throughout his career, Dr. Cornely was an outspoken advocate for social justice. As a professor at Howard, he worked on many research projects focused on the racism of the healthcare system at the time, including one titled “A Study of Negro Nursing,” where he argued that the education and employment of Black doctors and nurses was an important solution for helping right the racial imbalance he saw.1

He also worked tirelessly at the university’s hospital to promote desegregation. In 1956, he took that argument to the country, spearheading the Imhotep National Conference, which called on healthcare leaders to promote racial equality and focused on legal and political strategies to help make desegregation a reality.3

Nearly a decade later, he saw his hard work come to fruition. In 1964, his calls to action helped play a role in the landmark Supreme Court decision Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, in which the court moved to desegregate hospitals nationwide.2 And the year before, Conely played a pivotal part in one of the biggest moments in the Civil Rights Movement.

Deeply inspired by the messages of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Cornely was actively involved in the Movement, and in 1963, he served as the local medical coordinator for the March on Washington, collaborating with hundreds of medical workers to ensure the health and safety of the nearly 250,000 march participants.1

By the late 1960s, he was more deeply involved in the American Public Health Association, serving on the group’s Committee on Integration in Health Services and, in March 1967, representing the APHA at the first nationwide conference on the health status of the “Negro.”3

He closed out the decade with even more firsts, becoming the first Black American to be elected president of the APHA. (3) A few years later, in 1972, he was awarded the Sedgwick Medal, one of the group’s highest honors, for his tireless work in the fields of medicine, public health, and social justice.3

A healthier future

Dr. Paul Cornely continued working toward a more equal healthcare landscape throughout his life, going on to review papers for scientific journals well into his 90s before dying in 2002 at the age of 96.3

Along the way, he led a fascinating and impactful life. Unfortunately, many of the disparities he noted in his work persist today, with similar solutions—including a focus on educating and employing doctors and nurses from diverse backgrounds—still being called for more than 70 years later.6

While the work for equality is far from over, the advocates of today can stand on the shoulders of Dr. Cornely and use his groundbreaking research and vision to help further the cause, allowing his legacy to live on in a more perfect world.