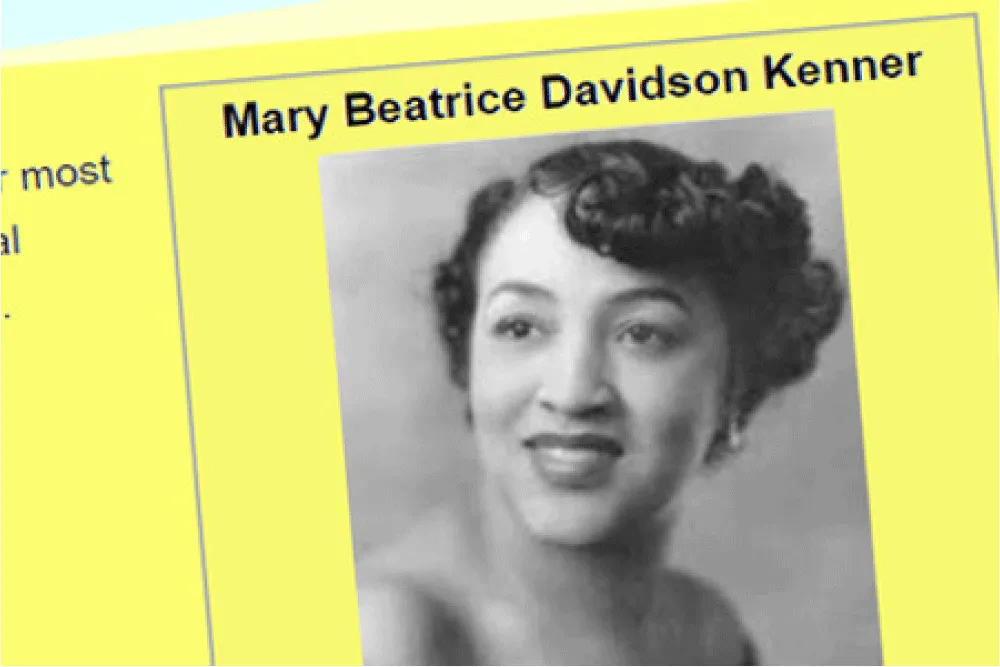

Born this way

In a way, it almost seems Kenner was destined for such a fate despite the hefty odds stacked against her. She came from a family of inventors, including her grandfather, who invented a light signal for trains; her father, who created and patented several inventions; and her sister, who created and patented board games.1 She also spent most of her life in Washington, D.C., not far from the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

By age six, she was reportedly already showing a knack for the family business, working on innovations like self-oiling hinges.1 And it wasn’t long before her cleverness helped earn her a spot at the renowned Howard University, though financial troubles meant she could never finish her schooling.

Thankfully, a formal education often has little to do with a formidable mind. Kenner kept at her passion, even after dropping out, and just over a decade later, in 1956, it led her to one of her most important innovations.

A change is going to come

It’s hard for many women to imagine life without the sanitary pads and tampons we use today. But remarkably, those innovations weren’t widely used until the 1980s.2

Tampons were once restricted primarily to medical use. They didn’t become widely available for personal use until the 1930s.3 Even after tampons were available, most women used more affordable and easy-to-obtain pads.

But early versions of pads were also different from the kind we have today. Before they had wings to help them cling to underwear, there was only a single adhesive strip on their back. Before the single adhesive strip was added, sanitary belts were used to help keep pads in place.2

Before the mid-century, these pads, by and large, weren’t disposable, either. Women commonly used cloth or other methods to trap menstrual blood. Keeping these less formal applications in place was a recurring, frustrating, and often embarrassing issue.

The shifting cotton cloths could occasionally become a hygienic concern, leading to leaks, chafing, irritation, and other issues.

Kenner’s invention helped put an end to all that.

Kenner's invention helped put an end to the issues and annoyances associated with the cotton cloths.

Step by step

Sanitary belts weren’t necessarily new, with the use of the tool being traced at least back to the 1800s.3 But Kenner’s work improved on the design.

Traditionally, the belt wrapped around a woman’s waist. It included two straps, one in the front and one in the back. These straps would end in clips meant to clip a cotton rag into place.

Kenner’s innovation made the belt adjustable, allowing women of all sizes to use the device comfortably or as comfortably as possible. She also did away with the clips, connecting the middle strap and thoughtfully adding a moisture-resistant pocket instead to help secure the pad or cloth.

In hindsight, it’s the kind of innovation that a woman could only imagine. Most men at the time likely had little idea or concern over what women went through every month. At the same time, most women were culturally encouraged to present themselves as “perfect,” to resist “complaining” about anything, let alone something as seemly as menstrual troubles, and to stay away from unpleasant conversations altogether.

But unfortunately—and also indicative of the times—it was the kind of woman Mary Kenner was that ultimately stood in the way of her success.

Fallout

In an early indication of how important the adjustable menstrual belt was thought to be, Kenner received no small amount of attention around her invention. One company in particular contacted Kenner to say they were sending a representative down to Washington, D.C., to speak with her personally about marketing the idea. (1)

But once they saw the color of her skin, they thought otherwise about following through.

“I was so jubilant... I saw houses, cars, and everything about to come my way," Kenner explained of the initial interest in one interview. “Sorry to say, when they found out I was Black, their interest dropped. The representative went back to New York and informed me the company was no longer interested."1

Instead, Kenner’s patent on the idea eventually lapsed, allowing manufacturers to use the design freely. Despite its comfort and hygienic value, she never made money on the adjustable belt.

{{link-bank-one-column}}

Moving forward

Yet, despite the setback, Kenner never stopped inventing. She secured five patents in her lifetime, the most of any Black woman.1

Her most famous innovation, the adjustable sanitary belt, maintains its place as a pivotal stepping stone in menstrual product history. The connected strap can easily be traced to pads secured by adhesive. And the values of a moisture-resistant pocket are also reflected in more modern products.

Kenner passed away in 2006 at the age of 93. And though she lived a long and full life, her innovative achievements were mostly unrecognized when she died.

Today, we work to reverse that oversight, helping bring to light inventions that helped change the world, even when their use, or inventors, may have made people uncomfortable. Because innovation, intelligence, and integrity should know no boundaries. And Mary Kenner’s work helped break so many of those barriers down.